But wait a minute, you might be saying if this interested you in the slightest, isn't the Federal Reserve out of gas? Haven't they done all that they can do? Having pushed down short-term interest rates on government debt about as low as it will or can go and having, in the meantime, swelled its balance sheet to an unprecedented level, isn't it's proverbial powder all soggied-up (or shot out, whatever you think is more appropriate to the context)?

I don't know, but Paul Krugman and a bunch of other people are mad. In fact, they're basically calling Ben Bernanke a pussy. So what's a central banker to do?

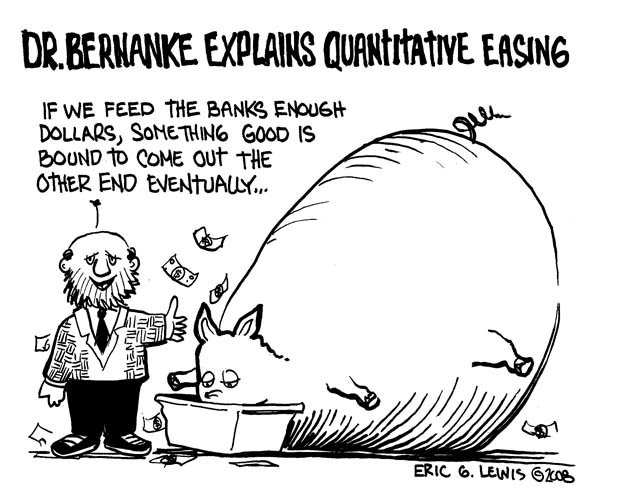

The most traditional approach would be to simply re-start what the Fed already did last year; to expand the range of assets the Fed will buy or otherwise deal with (from longer term U.S. government debt all the way out to financial toxic waste) and to re-open a lot of those fancy lending and asset buying facilities. There are an alphabet soup's worth of them, and they aren't really worth getting into because, fundamentally, they all serve the same purpose. Either through loans on rediculously easy terms or through the purchase of somewhat riskier assets, the Fed hands over to the banks (and a few other bankish things) a lot of cash. And if these banks have more cash, so the logic goes, they'll be less likely to sit on it and more likely to lend it out for, one can hope, productive, economically stimulating, purposes. Or they'll just use it all to lend back to the federal government which will in turn be prevented from spending it by Congress. But who's counting?

But, according to Nick Rowe, the particular menu of assets that the Fed decides to start devouring is not just about range, (i.e. how much more stuff it buys or how much risk it's willing to take on), but whether the particular assets in question are "pro-cyclical" (i.e. people tend to want and buy them when the economy is doing well and not so much when the economy is not so much doing well--think most stocks and, particularly this time around, houses, and, on a personal level, filet mignon) or "counter-cyclical" (think U.S. government debt, maybe gold, and McDonald's). Right now and traditionally, the Fed focuses on buying the most counter-cyclical of all counter-cyclical assets, short-term U.S. government debt. It's considered safe and it's ubiquitous as all hell--that's why the Fed deals in it. But, according to Rowe, that's exactly the wrong kind of asset to be buying now.

Suppose the Fed buys a counter-cyclical asset. If the price rises, people may interpret that rise as a sign that monetary policy is having the desired effect. Or they may interpret it as a sign the economy is getting weaker. Depending on how people interpret the rise in price of the counter-cyclical asset, and the relative strengths of the direct causal effect...the net effect on the economy is ambiguous....Suppose the Fed buys a pro-cyclical asset. If the price rises, people will interpret that as a sign that monetary policy is having the desired effect. Or they may interpret it as a sign the economy is getting stronger. Both effects work in the same, desired, direction. Also, if people thought that monetary policy was having the desired effect, and was not impotent, any increased optimism about the future path of the economy would tend to raise the price of the pro-cyclical asset still further, which would tend to make monetary policy look more effective, and reinforce that optimism. (Worthwhile Canadian Initiative)A bit more interesting to me, and a whole lot less likely, is the suggestion of junking and then rebuilding the entire way way in which monetary policy is conducted. As I mentioned before, all the money that the central bank hopes to push into the economy through an expansive policy is funneled through the banking system. In short: federal reserve gives cash to/buy something from a national bank, and then the bank feels a little bit freer to do the same to you and me. The obvious catch, however, is that it doesn't matter how much cash a bank has, the 0% return offered by cash (or the slightly higher yield offered by a loan to the U.S. government) beats the hell out of the expected return from you and me, because you and me are both unemployed and over-indebted. I mentioned this back in January.

Also, to the extent that Rowe and others talk about the influence of higher asset prices on inflation expectation (i.e. how people respond in their spending and investment behavior to an increase in prices), the respective directions of the financial markets and of the economy at large seem prone enough to dramatic divergence (at least for longish periods of time). Which is to say, even if stocks are up, that doesn't mean we all get our jobs back.

So here's an idea from Interfluidity: rather than relying on the financial sector to serve as a conduit, why not approximate Milton Freidman's helicopter drop by simply depositing chunks of cash in the bank accounts of citizens across the country. Yeah, just like that. Give money away. For free.

That is, rather than trying to fine-tune wages, asset prices, or credit, central banks should be in the business of fine tuning a rate of transfers from the bank to the public. During depressions and disinflations, the Fed should be depositing funds directly in bank accounts at a fast clip. During booms, the rate of transfers should slow to a trickle. We could reach the “zero bound”, but a different zero bound than today’s zero interest rate bugaboo. At the point at which the Fed is making no transfers yet inflation still threatens, the central bank would have to coordinate with Congress to do “fiscal policy” in the form of negative transfers, a.k.a. taxes.(Interfluidity)How would ensure an equal distribution of transfers? Would this create accounting issues for the Federal Reserve? What would be the optimal amount and how would we prevent people from abusing the system? The blogger, Steve Waldman, tries to address the practical questions, as if anyone would really humor the idea, or, more likely, just for the coherency the argument; it's a thought experiment for its own sake.

Which, for the time being, is what all of this is. In his last speech (which I didn't read; I'm boring, but not that boring), the Chairman Ben himself claimed that should the economy need additional help, the Fed would be willing to provide it. What that assistance would look like (and more pressingly, what an economy in need of help looks like the Fed) is, of course, just a matter of speculation.

No comments:

Post a Comment