It’s easy to look at the protesters and the politicians in Greece — and at the other European countries with huge debts — and wonder why they don’t get it. They have been enjoying more generous government benefits than they can afford. No mass rally and no bailout fund will change that. Only benefit cuts or tax increases can.Pretty different. This would be a prime example of why questions dredged from the back of one's mind should not provide the premises of front page news articles.

Yet in the back of your mind comes a nagging question: how different, really, is the United States?

For one, Greece is not the United States. There are a few important distinctions one could make. Greece is much more corrupt than the United States. Greece has much higher tax avoidance than the United States. Greece has much more unstable economic, fiscal, financial, and political record than the United States.

And then there are a few really important distinctions one could make. Greece has a lot more debt then the United States. Greece doesn't use the world's safe-haven currency which, incidentally, is that of the United States. Greece can't hypothetically depreciate out of the crisis as could, in the worst case scenario, the United States.

This is to say nothing of Leonhardt's casual reference to the other PIIGS-members. As Paul Krugman has written over and over, the problem facing countries like Spain and Portugal are not problems of fiscal irresponsibility. To try and moralize on the dangers of government debt based on the crisis (crises) facing Europe is misguided at best and dishonest at worst.

My quibble isn't with the overall thesis of Leonhardt's article; the U.S. has a lot of debt and we're going to have to deal with it sooner or later. Furthermore, it's nice to see an analysis of U.S. federal debt that talks about taxes and entitlement spending and not just welfare bums using government checks to get abortions and gay marriages. But I find the framing irresponsible. Presenting the crisis as a crisis of government excess feeds a particular political narrative that I find, given the current unemployment crisis the U.S. still faces, given the current state of our infrastructure and healthcare and education systems, fairly dangerous. Leonhardt also does very little to distinguish between the U.S. government's short-term budgetary issues (which result primarily from a drop-off in revenue and which ought to be addressed with more stimulus spending) and the government's long-term debt crisis (which, as Leonhardt correctly points out, has to be tackled with a combination of spending reductions on entitlement programs and tax increases). But again, in failing to clearly make this distinction, he provides fodder to those who are calling for spending cuts now and across the board.

Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong pick it up from there.

First, Krugman:

I would really question this comparison:

The numbers on our federal debt are becoming frighteningly familiar. The debt is projected to equal 140 percent of gross domestic product within two decades. Add in the budget troubles of state governments, and the true shortfall grows even larger. Greece’s debt, by comparison, equals about 115 percent of its G.D.P. today.

Um, that’s comparing a (highly uncertain) projection of debt 20 years from now — a projection that’s based on the assumption of unchanged policy — with actual debt now. Actual US federal debt is only about half that high now. And it’s worth pointing out that Greek debt is projected to rise to 149 percent of GDP over the next few years — and that’s with the austerity measures agreed with the IMF.

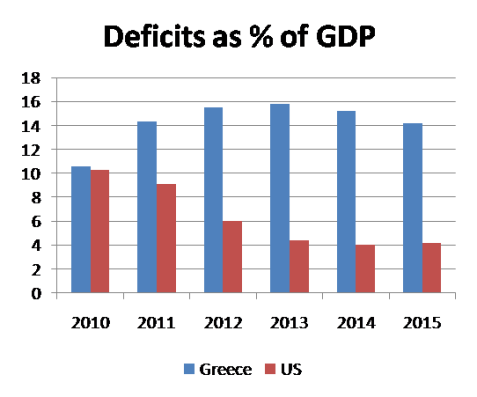

Here’s a more or less apples-to-apples comparison of the medium-term outlook. I’ve taken the Auerbach-Gale projections for the US budget deficit as a percentage of GDP outlook under Obama policies, and compared them with the IMF projections for Greece, subtracting out “measures” — that is, the austerity measures agreed in return for official loans. Here’s what it looks like:

And DeLong:

1) Starting around 2020 the U.S. has to finally solve the problem that Ronald Reagan created in the 1980 presidential campaign with his claim that the federal government could tax like Alabama and spend like Connecticut and somehow everything would work out. It won't. The U.S. has another decade to decide whether it wants to tax like Alabama and spend like Alabama, or tax like Connecticut and spend like Connecticut.

2) Financial markets continue to be astonishingly confident that the U.S. will in fact solve this problem: U.S. Treasury bonds continue to sell at astonishingly high valuations.

3) As long as unemployment is unduly elevated--above 7.5%, say--our major economic ill connected with big deficits is not excessive deficits forecast for the 2020s and beyond but excessive unemployment and idle capacity now.

4) An even larger U.S. budget deficit now would be a useful tool to help cure our major current economic ill by booting demand: right now the problem is not that our deficit is too large for the economy but that it is too small.

5) Some fear that large deficits today are undermining financial market confidence in the long-term fiscal stability of the United States. So far there are absolutely no--absolutely no--signs in financial markets that our current large deficits: U.S. Treasury bonds continue to sell at astonishingly high valuations.

6) Should financial markets begin at some point in the future to lose confidence in the long-term fiscal stability of the United States, that does not mean that the United States turns into Greece. Greece does not control the currency in which its government borrows. The U.S. does. That makes a huge difference.

By my count, David Leonhardt makes point (1) at great length, makes point (2) very briefly, doesn't make point (3) at all, doesn't make point (4) at all, doesn't make point (5) at all, and doesn't make point (6) at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment