Monday, May 31, 2010

Can I just say one thing real quick?

(Of course, Israel fucked up bad in the end. But really, people. I hate the tired old "Israeli-double-standard" yarn, but this is just ridiculous.)

EDIT: I love when the first actual analysis I read backs me up, and when it's recommended to me by Josh Marshall: link

Friday, May 28, 2010

House passes bill with DADT repeal provision

The House voted to pass the annual Pentagon Policy Bill which this year contains a provision for the repeal of the ban on openly gay and lesbian servicemen and servicewomen (Don't Ask, Don't Tell). The way it would work is that heads of the armed forces would be forced to remove the policy 60 days after they receive a report that basically states that having teh gayz in the military would not disrupt activities and policies. Whew.

The NYT article I linked also reports that there is still a chance that the bill will be vetoed by Obama based on funding for F-35 fighter. Because it's a major military policy bill, there are also delightful things like billions of dollars for military development etc. as well as $159 billion for overseas military operations, so...

Still, this is exciting!

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Alright, everybody out of the pool.

Well, shit:

A North Korean submarine's torpedo sank a South Korean navy ship on 26 March causing the deaths of 46 sailors, an international report has found.For the non-Bens in the audience, this shit went down back in March, and the international report was released today. Speculation has been heavy from the beginning that it was a North Korean torpedo that sunk the Cheonan, and now we have fairly conclusive evidence that that was, in fact, the case. What happens next, I don't really know. I've been told that the release of the report coincides suspiciously with the June local elections, but considering the length of time that has passed since the incident, plus the multinational nature of the investigation, that seems somewhat implausible. My guess is things went deliberately slowly because no one wanted this to spiral out of control and because South Korea is highly opposed to any military escalation. In fact, it doesn't seem to me like anyone wants a military escalation. If this was a deliberate, from-the-top kind of attack, then North Korea was probably doing what it's done so well in the past, playing the crazy card to get aid and relief from sanctions. It's equally likely, though, that it was unplanned and spontaneous, the kind of thing one would expect from a navy that believes that its opponents have horns and drink children's blood.

Investigators said they had discovered part of the torpedo on the sea floor and it carried lettering that matched a North Korean design.

All that said, I really don't know what kind of effect more sanctions will have, even if the Chinese are on board for this round. The Kim dynasty is absurdly resilient, and sanctions haven't had much of an effect on North Korea's actions or proclamations. They've also responded antagonistically to the report, suggesting that any sanctions will be interpreted as aggression. This only boxes Lee Myung-Bak in more; after weeks and weeks of wall-to-wall grief porn on every television station in this country mourning the lost sailors, he won't be able to get away with some toothless sanctioning and menacing statements. It's certainly possible that Ben and I may be home sooner than we thought.

Anyway, here's a good summary of the situation, even though it was written weeks before the report came out. This is a fascinating international crisis. If only I wasn't living in it.

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

Periods are kind of like the oil spill, right?

For starters, here's an interesting article on the adverse health effects of hormonal birth control.

Then there's this. Have any of you heard about this new form of birth control...for men?! Zapping the testicles with ultrasound waves is apparently a safe way to halt sperm production. I remember a few years ago there was all this hoopla about a birth control pill for men, but very little seems to have come of that. This, however, seems like it might be a thing.

So what do you think, gentleman? Would you try it?

(both links via Re:Cycling)

Monday, May 17, 2010

Details on the Spill

Friday, May 14, 2010

Don't hate the player, hate the game

Some have criticized Elena Kagan for supposedly favoring a strong view of executive power. They equate her views with support for the Bush Administration’s policies related to the “war on terror.” Generally speaking, these critics very significantly misunderstand what Kagan has written.Anyway, I'm getting away from myself. What I really wanted to talk about was the "ambitious" in "ambitious softball-playing lesbian".

Kagan’s only significant discussion of the issue of executive power comes in her article Presidential Administration, published in 2001 in the Harvard Law Review. The article has nothing to do with the questions of executive power that are implicated by the Bush policies – for example, power in times of war and in foreign affairs. It is instead concerned with the President’s power in the administrative context – i.e., the President’s ability to control executive branch and independent agencies. That kind of power is concerned with, for example, who controls the vast collection of federal agencies as they respond to the Gulf oil spill and the economic crisis.

Nor does the article assert that the President has “power” over the other branches of government in the constitutional sense – i.e., a power that cannot be overridden. To the contrary, Kagan “accept[s] Congress’ broad power to insulate administrative activity from the President.” (2251). She instead makes the descriptive claim “that Congress has left more power in Presidential hands than generally is recognized.” (Id.)

This sharp post got me thinking about it. Jonathan Bernstein's point, for the short of reading, is that Kagan is being unfairly maligned for being ambitious, when being ambitious is just a given for those who seek federal office. It's a fair criticism, and fairer still when you think of how uncontroversial an argument it is. Can you possibly imagine a scenario in which an unambitious person wound up president? Maybe if the president and the first 30-40 people in the line of succession were all swallowed whole in a Sarlacc pit, there would be a slight chance that you'd wind up with a replacement president of minimal political appetites. Even then, a stretch.

This isn't to say unqualified people can't occupy political office, just that ambition is essentially a qualification. Those without ambition, be it personal or ideological, just aren't going to get involved. So attacking a politician for being ambitious is, to me, kind of like attacking a politician for being unprincipled. If it makes good political sense for someone to flip and flop all over the place, why wouldn't they? Obviously it's scummy, just like how ambition can be scummy as well, but unless we return to some kind of monarchical system that limits the ranks of the political elite significantly, we're stuck with it. Even then, people are going to keep trying to take the throne, they're just going to use a lot more swords.

Bernstein makes this argument, but it bears repeating: if we fear the rise of judges who hide their paper trails because of their ambition, then we have to change the system of Supreme Court nomination to make hidden paper trails a liability. Ambition is a structural fact of political life and of human nature. Smart people are always going to look at what they want, figure out how to get it, and pursue that strategy, and if the dominant strategy for entering the Supreme Court is to keep your mouth shut as much as possible then that's what tons and tons of judges are going to do. I know that there are strong partisan reasons that would seem to preclude rules reform, but even small things, like a requirement that the nominee had taken a public stand on a certain number of significant issues, could really get rid of this problem. Until that happens, however, talking about the ambitions of a Supreme Court nominee is like talking about a marathon runner's legs: of course they've got them.

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Light, blessed light

Poll: Most oppose Reagan on the $50 billOver at the LRB, August Kleinzahler does a very good job of summing up why you should not be tempted to good thoughts about the Gipper, ever. I am relieved by the fact that, however hard the G.O.P. might still be beating the drum of deification, Americans are, for once, too conservative to agree.Rep. Patrick McHenry (R-N.C.) last month proposed putting Ronald Reagan on the $50 bill instead of former president Ulysses S. Grant, arguing that the "last great president" of the 20th century deserved the honor.

But 79 percent of Americans oppose the idea, according to a Marist Poll released Thursday. Only 12 percent support McHenry's idea while 9 percent are unsure.

Perhaps most notably, 71 percent of Republicans oppose the idea, an interesting statistic considering the Gipper's GOP hero status. Among Democrats, 83 percent don't want Grant replaced and 79 percent of independents agree.

Oh, I am a buttface stupidpants!

Slightly more intriguing, as I recently finished writing about the Gilded Age, is this video about how Ford can't build an truly "advanced" automobile plant because Labour doesn't like it. This is probably true. All of us who had so much fun during the Carnegie Steel Strikes know that Vertical Integration is the best way to increase national industrial output - the country almost entirely halted its industrial growth following the Progressive reforms at the turn of the century and the communist revolution that we didn't have. Fuck fancy cars, if we hadn't pussied out to Labour, we might make most superior potassium on planet! I think my favorite part, though, is the implication that the American auto industry is being held back because Ford is forced to outsource its best work to our samba-loving neighbors. If only our workers would accept exploitative quasi-trusts to operate in our country, maybe Toyota would come and open a plant here! (The comments drive me wild!)

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

David Leonhardt Writes a Stupid Thing

It’s easy to look at the protesters and the politicians in Greece — and at the other European countries with huge debts — and wonder why they don’t get it. They have been enjoying more generous government benefits than they can afford. No mass rally and no bailout fund will change that. Only benefit cuts or tax increases can.Pretty different. This would be a prime example of why questions dredged from the back of one's mind should not provide the premises of front page news articles.

Yet in the back of your mind comes a nagging question: how different, really, is the United States?

For one, Greece is not the United States. There are a few important distinctions one could make. Greece is much more corrupt than the United States. Greece has much higher tax avoidance than the United States. Greece has much more unstable economic, fiscal, financial, and political record than the United States.

And then there are a few really important distinctions one could make. Greece has a lot more debt then the United States. Greece doesn't use the world's safe-haven currency which, incidentally, is that of the United States. Greece can't hypothetically depreciate out of the crisis as could, in the worst case scenario, the United States.

This is to say nothing of Leonhardt's casual reference to the other PIIGS-members. As Paul Krugman has written over and over, the problem facing countries like Spain and Portugal are not problems of fiscal irresponsibility. To try and moralize on the dangers of government debt based on the crisis (crises) facing Europe is misguided at best and dishonest at worst.

My quibble isn't with the overall thesis of Leonhardt's article; the U.S. has a lot of debt and we're going to have to deal with it sooner or later. Furthermore, it's nice to see an analysis of U.S. federal debt that talks about taxes and entitlement spending and not just welfare bums using government checks to get abortions and gay marriages. But I find the framing irresponsible. Presenting the crisis as a crisis of government excess feeds a particular political narrative that I find, given the current unemployment crisis the U.S. still faces, given the current state of our infrastructure and healthcare and education systems, fairly dangerous. Leonhardt also does very little to distinguish between the U.S. government's short-term budgetary issues (which result primarily from a drop-off in revenue and which ought to be addressed with more stimulus spending) and the government's long-term debt crisis (which, as Leonhardt correctly points out, has to be tackled with a combination of spending reductions on entitlement programs and tax increases). But again, in failing to clearly make this distinction, he provides fodder to those who are calling for spending cuts now and across the board.

Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong pick it up from there.

First, Krugman:

I would really question this comparison:

The numbers on our federal debt are becoming frighteningly familiar. The debt is projected to equal 140 percent of gross domestic product within two decades. Add in the budget troubles of state governments, and the true shortfall grows even larger. Greece’s debt, by comparison, equals about 115 percent of its G.D.P. today.

Um, that’s comparing a (highly uncertain) projection of debt 20 years from now — a projection that’s based on the assumption of unchanged policy — with actual debt now. Actual US federal debt is only about half that high now. And it’s worth pointing out that Greek debt is projected to rise to 149 percent of GDP over the next few years — and that’s with the austerity measures agreed with the IMF.

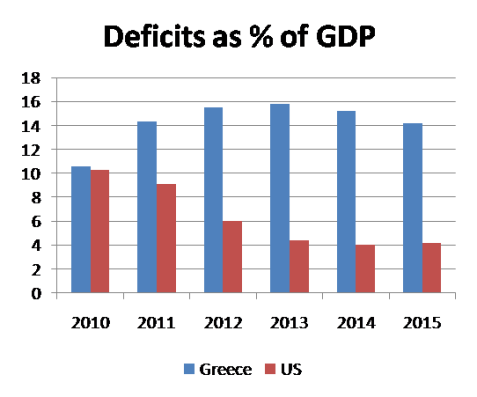

Here’s a more or less apples-to-apples comparison of the medium-term outlook. I’ve taken the Auerbach-Gale projections for the US budget deficit as a percentage of GDP outlook under Obama policies, and compared them with the IMF projections for Greece, subtracting out “measures” — that is, the austerity measures agreed in return for official loans. Here’s what it looks like:

And DeLong:

1) Starting around 2020 the U.S. has to finally solve the problem that Ronald Reagan created in the 1980 presidential campaign with his claim that the federal government could tax like Alabama and spend like Connecticut and somehow everything would work out. It won't. The U.S. has another decade to decide whether it wants to tax like Alabama and spend like Alabama, or tax like Connecticut and spend like Connecticut.

2) Financial markets continue to be astonishingly confident that the U.S. will in fact solve this problem: U.S. Treasury bonds continue to sell at astonishingly high valuations.

3) As long as unemployment is unduly elevated--above 7.5%, say--our major economic ill connected with big deficits is not excessive deficits forecast for the 2020s and beyond but excessive unemployment and idle capacity now.

4) An even larger U.S. budget deficit now would be a useful tool to help cure our major current economic ill by booting demand: right now the problem is not that our deficit is too large for the economy but that it is too small.

5) Some fear that large deficits today are undermining financial market confidence in the long-term fiscal stability of the United States. So far there are absolutely no--absolutely no--signs in financial markets that our current large deficits: U.S. Treasury bonds continue to sell at astonishingly high valuations.

6) Should financial markets begin at some point in the future to lose confidence in the long-term fiscal stability of the United States, that does not mean that the United States turns into Greece. Greece does not control the currency in which its government borrows. The U.S. does. That makes a huge difference.

By my count, David Leonhardt makes point (1) at great length, makes point (2) very briefly, doesn't make point (3) at all, doesn't make point (4) at all, doesn't make point (5) at all, and doesn't make point (6) at all.

Monday, May 10, 2010

Buy It!

Let's forget for a second that certain sovereign creditors of the U.S. government might have an interest in the continued (ostensible) solvency of Freddie or Fannie. Looking at the primary intent of these institutions (that is, to implicitly subsidize homeownership), along with various distortion in the national tax-code and federal subsidies to lenders, does it make any sense in the long-term to continue forwarding a national policy that is, in the words of Paul Krugman, "based on the premise that everyone should be a homeowner." (NYTimes)

An Edwardo Porter article from 2005 says no. Here are some excerpts:

Arguments for the positive effects from a society of homeowners - what economists call positive externalities - stem mainly from the fact that homeowners have a bigger financial stake in their homes than renters do. This motivates them, so the theory goes, to take better care of their houses and communities. In short, it will make them better Americans.

The argument seems to be supported by compelling evidence. In a 1998 study, Edward Glaeser, an economics professor at Harvard, and Denise DiPasquale, then a social scientist at the University of Chicago who now heads the housing research firm City Research, analyzed data from the General Social Survey, a big national study carried out annually since 1972, and concluded that homeownership did relate to heightened civic activity.

For instance, they found that 77 percent of homeowners said they had at some point voted in local elections, while only 52 percent of renters said they had. About 20 percent of renters knew the name of their representative on the school board; 38 percent of homeowners did. Homeowners went to church more, and invested more in the upkeep of their homes.

But as alluring as the data may be, economists and social scientists haven't been able to determine whether homeownership is actually generating all the positive statistics or whether, instead, it's just that people who vote more are more likely to buy homes.

Owning a home relates to a bunch of other things, too, and it doesn't necessarily mean that homeownership causes or encourages them. For instance, according to the 1998 study, homeowners are older, richer, more likely to vote Republican, and more than half of them own guns, while only a quarter of renters do.

[...]

Beyond the difficulty of proving that owning a home generates positive social spillover, homeownership may also affect society in negative ways.

Homeownership limits mobility. According to census data, 31 percent of renters moved in 2003, compared with about 7 percent of homeowners. While this stability can be good for a community, the reduced mobility can become a problem in the face of a local economic downturn.

And homeowners may influence social policy to benefit themselves, at the expense of others. In a study of voters in California in 2000, Mr. Glaeser found that homeowners were more likely to restrict new home-building, voting for tough zoning rules and land-use controls.

"Homeowners have spearheaded the movement to limit new housing supply that has artificially inflated housing throughout the U.S.," Mr. Glaeser wrote. "This is the downside to having individuals who have incentives to keep price up."

The tax incentives might even be hurting America's inner cities, increasing the segregation of rich and poor.

Mr. Gyourko and Richard Voith, a former economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia who is now a partner in Econsult, a consulting firm, have argued that the mortgage interest deduction encourages richer families to buy bigger places in the suburbs and leave the more cramped cities to the poor.

At least until recently, it seems that the social good of home-ownership--home-ownership for its own sake--has been taken for granted among both policy makers and academics. Seems kind of silly now.

Sunday, May 9, 2010

Not even a peep

What claim do we Americans make to citizenship in a democracy, anymore? I await the day when asking that question will produce an indifferent shoulder-shrug from any given respondent. That's when we'll know the door has shut for good behind us.

Beyond Petroleum

Now that the most recent attempt has failed to stop the oil from hemorrhaging into the Gulf--as it turns out, dropping a 98 ton milking machine on top of the leak is just as stupid as it sounds--it seems an appropriate time as any to re-assess the morbid assessments of just how bad this thing is going to be and just what we can expect our wizened representatives in government to do about it.

A week ago, Ezra Klein posted excerpts of the following report from Cumberland Investors. Beginning with the best-case scenario:

Containment chambers are put in place and they catch the outflow from the three ruptures that are currently pouring 200,000 gallons of oil into the Gulf every day. If this works, it will--At this point, I think we can comfortably skip ahead to the doomier and gloomier scenario:

This spew stoppage takes longer to reach a full closure; the subsequent cleanup may take a decade. The Gulf becomes a damaged sea for a generation. The oil slick leaks beyond the western Florida coast, enters the Gulfstream and reaches the eastern coast of the United States and beyond...Monetary cost is now measured in the many hundreds of billions of dollars. (Ezra Klein)For the Gulf economy in particular, to say nothing of the possible (let's say, likely) ecological catastrophe, we might be witnessing the end of the end for the region's fishing industry.

The Louisiana coast includes 3 million acres of wetlands that serve as a nursery for game fish such as speckled trout and red drum and are currently nurturing the brown shrimp crop to be harvested by the state’s fishing fleet.Louisiana is the largest seafood producer in the lower 48 states, with annual retail sales of about $1.8 billion, according to state data. Recreational fishing generates about $1 billion in retail sales a year, according to the state.

“Our marshes are nurseries and if those marshes are impacted, those juveniles that are dependent on feeding in those marshes will be affected too,” [Karen] Foote said in an interview...Those species include shrimp, oysters, crab, menhaden and game fish that have made Louisiana a destination for seafood lovers, commercial harvesters and anglers[.] (Business Week)

Oil production and fishing are two of Louisiana's largest industries. From an economic standpoint, B.P. might be finishing what Katrina started.

All oil comes from someone’s backyard, and when we don’t reduce the amount of oil we consume, and refuse to drill at home, we end up getting people to drill for us in Kazakhstan, Angola and Nigeria — places without America’s strong environmental safeguards or the resources to enforce them.

Kazakhstan, for one, had no comprehensive environmental laws until 2007, and Nigeria has suffered spills equivalent to that of the Exxon Valdez every year since 1969. (As of last year, Nigeria had 2,000 active spills.)...Effectively, we’ve been importing oil and exporting spills to villages and waterways all over the world. (New York Times)

Optimism for more far-sighted policy might not be entirely unfounded. Aside from the predictable revulsion and panic, my initial thoughts on the spill were that, coming so soon after the Massey coal mining disaster, it might prove to be a toxic contradiction sufficiently enormous and awful to catalyze real change. At the very least, the reasonable and naive spectator might hope, we should expect a series of re-regulation measures ranging from worker safety to environmental, if not a full upheaval in our national energy policy. This could be something as broad and patently necessary as Margonelli's set of off-the-cuff recommendations:

a comprehensive oil reduction dependency act that aligns highway policy with reducing subsidies with a loan program that allows middle-class people to get much more efficient cars to natural gas trucking to incentives for businesses to cut gas usage. (Ezra Klein)I suspect that the president's bully-pulpitting on this issue is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for change. But with the majority of the affected states boasting political representatives heavily financially dependent upon the petroleum industry and populations largely suspicious of federal regulation and reform, even if Obama should overcome his lack of credibility on this issue and discover his inner-Lyndon Johnson in the process, I find it difficult to prepare myself for anything other than disappointment.

Thursday, May 6, 2010

A very serious, thoughtful, argument that has never been made in such detail or with such care.

UPDATE: The necessary context, for the uninitiated, is here, here, and most importantly, here. I readily admit that I am something of a Goldberg obsessive, as his way of thinking always calls to mind some kind of similarly named overly complicated piece of machinery.

Sunday, May 2, 2010

Acronyms to Ponder

Until last week, I'd never heard of "IBGYBG." But during the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations' eye-opening hearings into ratings agency malfeasance, former Moody's senior credit officer Richard Michalek introduced me to it while testifying about the perverse incentives that dominated the industry. On the investment bank side, he said, bankers were looking to score the one-time fee from whatever securitization deal they were asking the agency to rate, and move on to the next deal. The incentives for the bank, Michalek said in prepared testimony, were clear: "get the deal closed, and if there's a problem later on, it was just another case of IBGYBG--I'll be gone, you'll be gone."

Michalek says he first heard the phrase from "an investment banker who was running out of patience" with his "insistence on a detailed review of the documentation."(The Nation)

Clever.